His colorless eyes sought mine. "I only wanted to demonstrate that I was correct. You said it was impossible to succeed as a Repairer of Reputations; that even if I did succeed in certain cases, it would cost me more than I would gain by it. To-day I have five hundred men in my employ, who are poorly paid, but who pursue the work with an enthusiasm which possibly may be born of fear.

These men enter every shade and grade of society; some even are pillars of the most exclusive social temples; other are the prop and pride of the financial world; still others hold undisputed sway among the 'Fancy and the Talent.' I choose them at my leisure from those who reply to my advertisements. It is easy enough -- they are all cowards. I could treble the number in twenty days if I wished. So, you see, those who have in their keeping the reputations of their fellow citizens, I have in my pay.""They may turn on you," I suggested.

He rubbed his thumb over his cropped ears and adjusted the wax substitutes.

"I think not," he murmured, thoughtfully, "I seldom have

to apply the whip, and then only once. Besides, they like their wages."

"How do you apply the whip?" I demanded. His face for a moment was awful to look upon. His eyes dwindled to a

pair of green sparks. "I invite them to come and have a little chat with me," he

said, in a soft voice. A knock at the door interrupted him, and his face resumed its amiable

expression. "Who is it?" he inquired. "Mr. Steylette," was the answer. "Come to-morrow," replied Mr. Wilde. "Impossible," began the other; but was silenced by sort of

bark from Mr. Wilde. "Come to-morrow," he repeated. We heard somebody move away from the door and turn the corner by the

stair-way. "Who is that?" I asked. "Arnold Steylette, owner and editor-in-chief of the great New York

daily." He drummed on the ledger with his fingerless hand, adding, "I pay

him very badly, but he thinks it is a good bargain." "Arnold Steylette!" I repeated, amazed. "Yes," said Mr. Wilde, with a self-satisfied cough. "Where are the notes?" I asked. He pointed to the table, and

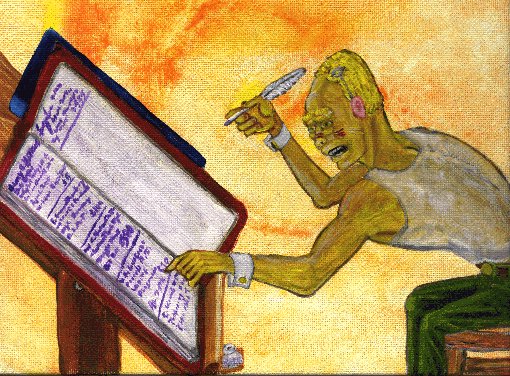

for the hundredth time I picked up the bundle of manuscript entitled "THE IMPERIAL DYNASTY OF AMERICA." One by one I studied the well-worn pages, worn only by my own handling,

and, although I knew all by heart, from the beginning, "when from

Carcosa, the Hyades, Hastur, and Aldebaran," to "Castaigne, Louis When I finished, Mr. Wilde nodded and coughed. "Speaking of your

legitimate ambition," he said, how do Constance and Louis get along?"

"She loves him," I replied, simply. The cat on his knee suddenly turned and struck at his eyes, and he flung

her off and climbed onto the chair opposite me. "And Dr. Archer? But that's a matter you can settle any time you

wish," he added. "Yes," I replied, "Dr. Archer can wait, but it is time

I saw my cousin Louis." "It is time," he repeated. Then he took another ledger from

the table and ran over the leaves rapidly. "We are now in communication with ten thousand men," he muttered.

"We can count on one hundred thousand within the first twenty-eight

hours, and in forty-eight hours the State will rise en masse. The

country follows the State, and the portion that will not, I mean California

and the Northwest, might better never have been inhabited. I shall not

send them the Yellow Sign." The blood rushed to my head, but I only answered, "A new broom

sweeps clean." "The ambition of Caesar and of Napoleon pales before that which

could not rest until it had seized the minds of men and controlled even

their unborn thoughts," said Mr. Wilde. "You are speaking of the King in Yellow," I groaned, with

a shudder. "He is a king whom emperors have served." "I am content to serve him," I replied. Mr. Wilde sat rubbing his ears with his crippled hand. "Perhaps

Constance does not love him," he suggested. "Yes," he said, "it is time that you saw your cousin

Louis." He unlocked the door and I picked up my hat and stick and stepped into

the corridor. The stairs were dark. Groping about, I set my foot on something

soft, which snarled and spit, and I aimed a murderous blow at the cat,

but my cane shivered to splinters against the balustrade, and the beast

scurried back into Mr. Wilde's room. Passing Hawberk's door again, I saw him still at work on the armor,

but I did not stop, and, stepping out into Bleecker Street, I followed

it to Wooster, skirted the grounds of the Lethal Chamber, and, crossing

Washington Park, went straight to my rooms in the Benedick. Here I lunched

comfortably, read the Herald and the Meteor, and finally

went to the steel safe in my bedroom and set the time combination. The

The cat, which had entered the room as he spoke, hesitated, looked up

at him, and snarled. He climbed down from the chair, and, squatting on

the floor, took the creature into his arms and caressed her. The cat ceased

snarling and presently began a loud purring, which seemed to increase in

timbre as he stroked her.

The cat, which had entered the room as he spoke, hesitated, looked up

at him, and snarled. He climbed down from the chair, and, squatting on

the floor, took the creature into his arms and caressed her. The cat ceased

snarling and presently began a loud purring, which seemed to increase in

timbre as he stroked her.

de Calvados, born December 19, 1887," I read it with an eager, rapt

attention, pausing to repeat parts of it aloud, and dwelling especially

on "Hildred de Calvados, only son of Hildred Castaigne and Edythe

Landes Castaigne, first in succession," etc., etc.

de Calvados, born December 19, 1887," I read it with an eager, rapt

attention, pausing to repeat parts of it aloud, and dwelling especially

on "Hildred de Calvados, only son of Hildred Castaigne and Edythe

Landes Castaigne, first in succession," etc., etc.

I started to reply, but a sudden burst of military music from the street

below drowned my voice. The Twentieth Dragoon Regiment, formerly in garrison

at Mount St. Vincent, was returning from the manoeuvres in Westchester

County to its new barracks on East Washington Square. It was my cousin's

regiment. They were a fine lot of fellows, in their pale-blue, tight-fitting

jackets, jaunty busbies, and with riding-breeches, with the double yellow

stripe, into which their limbs seemed to have been moulded. Every other

squadron was armed with lances, from the metal points of which fluttered

yellow-and-white pennons. The band passed, playing the regimental march,

then came the colonel and staff, the horses crowding and trampling, while

their heads bobbed in unison, and the pennons fluttered from their lance

points. The troopers, who rode with the beautiful English seat, looked

brown as berries from their bloodless campaign among the farms of Westchester,

and the music of their sabres against the stirrups, and the jingle of spurs

and carbines was delightful to me. I saw Louis riding with his squadron.

He was as handsome an officer as I have ever seen. Mr. Wilde, who had mounted

a chair by the window, saw him, too, but said nothing. Louis turned and

I started to reply, but a sudden burst of military music from the street

below drowned my voice. The Twentieth Dragoon Regiment, formerly in garrison

at Mount St. Vincent, was returning from the manoeuvres in Westchester

County to its new barracks on East Washington Square. It was my cousin's

regiment. They were a fine lot of fellows, in their pale-blue, tight-fitting

jackets, jaunty busbies, and with riding-breeches, with the double yellow

stripe, into which their limbs seemed to have been moulded. Every other

squadron was armed with lances, from the metal points of which fluttered

yellow-and-white pennons. The band passed, playing the regimental march,

then came the colonel and staff, the horses crowding and trampling, while

their heads bobbed in unison, and the pennons fluttered from their lance

points. The troopers, who rode with the beautiful English seat, looked

brown as berries from their bloodless campaign among the farms of Westchester,

and the music of their sabres against the stirrups, and the jingle of spurs

and carbines was delightful to me. I saw Louis riding with his squadron.

He was as handsome an officer as I have ever seen. Mr. Wilde, who had mounted

a chair by the window, saw him, too, but said nothing. Louis turned and looked straight at Hawberk's shop as he passed, and I could see the flush

on his brown cheeks. I think Constance must have been at the window. When

the last troopers had clattered by, and the last pennons vanished into

South Fifth Avenue, Mr. Wilde clambered out of his chair and dragged the

chest away from the door.

looked straight at Hawberk's shop as he passed, and I could see the flush

on his brown cheeks. I think Constance must have been at the window. When

the last troopers had clattered by, and the last pennons vanished into

South Fifth Avenue, Mr. Wilde clambered out of his chair and dragged the

chest away from the door.

three and three-quarter minutes which it is necessary to wait, while the

time lock is opening, are to me golden moments. From the instant I set

the combination to the moment when I grasp the knobs and swing back the

solid steel doors, I live in an ecstasy of expectation. Those moments must

be like moments passed in paradise. I know what I am to find at the end

of the time limit.

three and three-quarter minutes which it is necessary to wait, while the

time lock is opening, are to me golden moments. From the instant I set

the combination to the moment when I grasp the knobs and swing back the

solid steel doors, I live in an ecstasy of expectation. Those moments must

be like moments passed in paradise. I know what I am to find at the end

of the time limit.  I know what the massive safe holds secure for me, for

me alone, and the exquisite pleasure of waiting is hardly enhanced when

the safe opens and I lift, from its velvet crown, a diadem of purest gold,

blazing with diamonds. I do this every day, and yet the joy of waiting

and at last touching again the diadem only seems to increase as the days

pass. It is a diadem fit for a king among kings, an emperor among emperors.

The King in Yellow might scorn it, but it shall be worn by his royal servant.

I know what the massive safe holds secure for me, for

me alone, and the exquisite pleasure of waiting is hardly enhanced when

the safe opens and I lift, from its velvet crown, a diadem of purest gold,

blazing with diamonds. I do this every day, and yet the joy of waiting

and at last touching again the diadem only seems to increase as the days

pass. It is a diadem fit for a king among kings, an emperor among emperors.

The King in Yellow might scorn it, but it shall be worn by his royal servant.